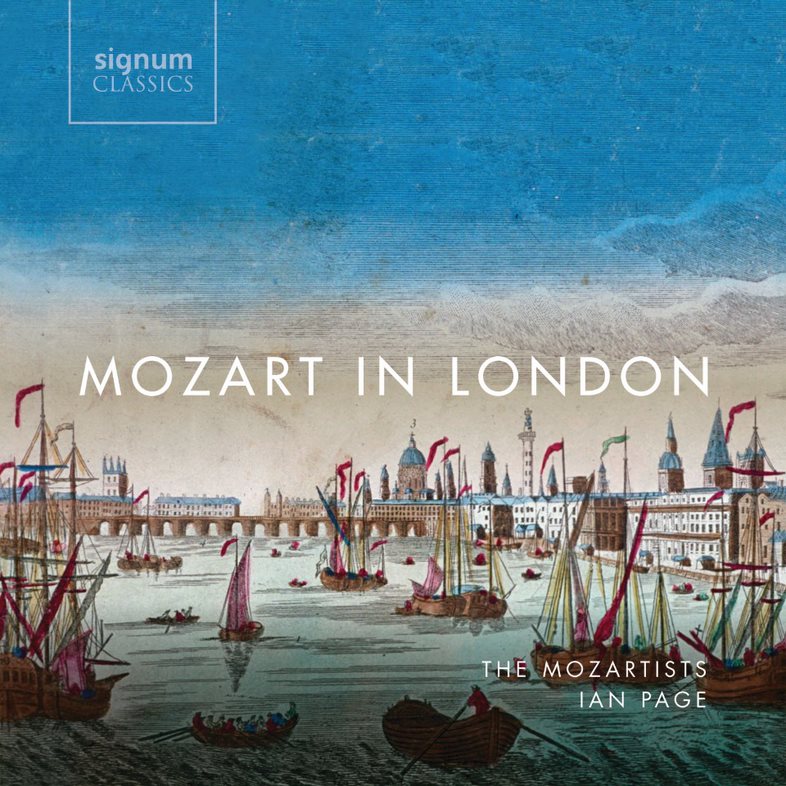

“A wonderful exploration of the musical life of London during Mozart’s visit as an eight year old, all beautifully and engagingly performed by Ian Page and his Mozartists. A true delight!”

GRAMOPHONE

“One of its constant pleasures is the young British performers’ sheer gusto… And the music itself? Delicious.”

THE TIMES

This 2-CD set presents an unprecedented survey of Mozart’s childhood visit to London in 1764-65. Ian Page conducts his outstanding period-instrument orchestra in a fascinating and wide-ranging programme which includes Mozart’s remarkable first symphony (composed when he was eight years old), along with his two other London symphonies and his first concert Aria. The repertoire also explores the music that was being performed in London during Mozart’s stay, including works by J. C. Bach, Thomas Arne, Abel, Pescetti, Perez, George Rush and William Bates, many of which have not previously been recorded, and the large cast of soloists includes eight singers and harpsichordist Steven Devine.

To order your copy, please click the ‘Add to cart’ button or download a digital version from one of the sites below:

CD 1

- Mozart: Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, K16 – I. Molto allegro5.39

- Mozart: Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, K16 – II. Andante4.57

- Mozart: Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, K16 – Presto1.33

- Arne: Judith – Act II: “Sleep, gentle Cherub! Sleep descend”3.01

- Arne: Judith – Act I: “O torment great, too great to bear”3.46

- Arne: Artaxerxes – Act I, Scene 2: “Amid a thousand racking Woes”4.47

- Arne: Artaxerxes – Act I, Scene 13: “O too lovely, too unkind”4.35

- Bach, J C: Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Op. 1 No. 6 – I. Allegro assai4.44

- Bach, J C: Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Op. 1 No. 6 – II. Andante3.31

- Bach, J C: Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Op. 1 No. 6 – III. Allegro moderato2.54

- Bach, J C: Ezio: “Non so d’onde viene”8.26

- Bach, J C: Berenice – “Confusa, smarrita”5.56

- Arne: The Guardian Outwitted – “O Dolly, I part”2.35

- Arnold, S: The Maid of the Mill – Act III, Scene 1: “To speak my mind of womankind”1.02

- Arnold, S: The Maid of the Mill – Act II, Scene 8: “Hist, hist! I hear my mother call”1.54

- Mozart: Symphony No. 4 in D major, K19 – I. Allegro2.18

- Mozart: Symphony No. 4 in D major, K19 – II. Andante3.55

- Mozart: Symphony No. 4 in D major, K19 – III. Presto2.49

- Pescetti: Ezio – “Caro mio bene, addio”9.02

CD 2

- Mozart: Symphony in F Major, K. 19a – Allegro assai4.59

- Mozart: Symphony in F Major, K. 19a – II. Andante 4.58

- Mozart: Symphony in F Major, K. 19a – III. Presto1.29

- Bach, J C: Adriano in Siria – “Ah, come mi balza il cor!”2.09

- Bach, J C: Adriano in Siria – “Deh lascia, o ciel pietoso”6.22

- Bach, J C: Adriano in Siria – Act II; “Cara la dolce amma”8.50

- Rush, G: The Capricious Lovers – Act I, Scene 8: “Thus laugh’d at, jilted and betray’d”2.37

- Bates, W: Pharnaces – “In this I fear my latest breath”2.41

- Mozart: Va, dal furor portata, K216.14

- Perez, D: Solimano – “Se non ti moro a lato”9.28

- Abel, C F: Symphony in E-Flat Major, Op. 7 No. 6 – Allegro3.39

- Abel, C F: Symphony in E-Flat Major, Op. 7 No. 6 – Andante5.28

- Abel, C F: Symphony in E-Flat Major, Op. 7 No. 6 – Presto2.54

Mozart in London – an introduction by Ian Page

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart arrived in London with his father, mother and sister on 23 April 1764, and remained there for fifteen months. During this period he gave numerous public concerts in addition to three private performances for King George III and Queen Charlotte, and he was exposed to a wide variety of other people’s music, some of which (unsurprisingly) had an important effect on the evolution of his own compositional style. It was while he was in London that Mozart composed his first symphonies and his first aria.

The London to which he came was of course vastly different from the modern city. It was the largest, busiest and wealthiest city in the world, and the recent 1761 Westminster Paving Act, which provided street lamps that burned throughout the night, merely added to the impression of a metropolis that never slept. It was the London of Dr Johnson and Horace Walpole, of David Garrick and Pitt the Elder. Handel, who lived in London for the last forty-seven years of his life, had died only five years previously, and Hogarth passed away during the Mozarts’ stay. Only two bridges – London and Westminster – spanned the Thames (Blackfriars Bridge was under construction but was not opened to the public until 1766), and Buckingham Palace (or Buckingham House, as it was then called), had been built by the Duke of Buckingham as recently as 1703, and had only been bought by the Crown in 1720.

Mozart’s father, Leopold, was a violinist and composer at the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg, but his name was known beyond Salzburg and Augsburg (the town of his birth) only as a result of his highly-regarded treatise on the art of violin-playing, which had been published in 1756. In 1747 he had married Maria Anna Pertl, who bore him seven children; of these only the fourth, Nannerl, and the last, Wolfgang, survived infancy. Leopold soon realised that both these children had exceptional gifts, and he started to devote all his energies and spare time to their musical education – a task for which he was eminently qualified.

Following a highly successful visit to Munich and Vienna – where the children played for the Empress Maria Theresia at Schönbrunn Palace – Leopold and his family set off on a Grand Tour, departing from Salzburg on 9 June 1763. Their ensuing itinerary included Munich (again), Augsburg, Ludwigsburg, Schwetzingen, Mannheim, Mainz, Frankfurt, Cologne, Brussels and Paris, where they stayed for six months (including a fortnight at Versailles).They had not originally intended to travel any further north but, in Leopold’s own words, “everyone, even in Paris, urged us to go to London”. They left Paris on 10 April 1764, arriving in Calais on 19 April. It was the first time that they had seen the sea.

The crossing to Dover, in a small chartered boat which they shared with four other passengers, was a torrid affair – in a letter to his landlord in Salzburg Leopold wrote: “Thank God we have safely crossed the Channel. Yet we have not done so without making a heavy contribution in vomiting” – and after spending one night in Dover they finally arrived in London on 23 April. Mozart’s father was forty-four, his mother forty-three, and his sister Nannerl (whom many considered to be an even finer keyboard player than her brother) twelve. Wolfgang was eight.

The Mozarts spent their first night at the White Bear Inn on Piccadilly, and the next day they moved into lodgings above a barber’s shop owned by a John Cousins on Cecil Court, just off St Martin’s Lane. It was a bad time of year to arrive in London – the opera season had finished and many potential patrons had retired to the countryside for the summer months – but within three days, on 27 April, Wolfgang and Nannerl were performing for the King and Queen at Buckingham House. This seems to have been a great success, with Leopold observing that “here our welcome surpassed all others”, and they were invited to return on 19 May. On this second visit Wolfgang sight-read keyboard works by Abel, J. C. Bach and Handel before accompanying Queen Charlotte singing an aria. “Lastly”, his father reported, “he took the bass part of some Handel arias, which happened to be lying there, and above this plain bass he improvised the most beautiful melody, in such a manner that everyone was astonished.”

On 5 June the children gave their first public concert in the city, at the Great Room in Spring Garden (near St James’s Park), and on 20 June Wolfgang performed in a charity concert at Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens, situated in what are now the grounds of the Royal Chelsea Hospital. The following month, however, Leopold Mozart caught a chill on the way home from a concert at the Earl of Thanet’s house in Grosvenor Square. His letters again provide colourful detail:

“In England there is a kind of native complaint, which is called a ‘cold’. That is why you hardly ever see the people here wearing summer clothes. In the case of those whose constitution is not strong, this so-called ‘cold’ becomes so dangerous that in many cases it develops into a ‘consumption’, as they call it here… and the wisest course of action for such people to take is to leave England altogether and to cross the sea. Indeed, many cases can be found of people recovering their health on leaving this country.”

Leopold’s own prescription was not quite so drastic, but he was advised to withdraw to the cleaner air of the countryside. As a result the Mozart family moved to Chelsea on 6 August, to a house belonging to a Dr Randal in Five-Fields Row (now 180 Ebury Street). It seems hard to believe now that this location was sufficiently removed from the city to have the desired effect, but the street-name suggests that the area was far more rural in the 1760s than it is now. It was here that Mozart composed his first symphony, and the family remained there until late September, when they returned to the centre of town, taking up lodgings at the house of Mr Thomas Williamson, corset-maker, at 15 Thrift Street (on the site of what is now 20 Frith Street). The Mozart children performed for the third and final time at Buckingham House on 25 October, the fourth anniversary of the King’s accession to the throne, and Wolfgang subsequently composed a set of six keyboard sonatas (with optional parts for violin and cello), which were completed on 18 January 1765, published on 20 March, and dedicated to Queen Charlotte.

The artistic and social whirl of the city was now in full swing too, and there were numerous opportunities for the children to continue their unique education. They visited many of London’s most celebrated landmarks, including Westminster Abbey, St Paul’s Cathedral, the Foundling Hospital, the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and the recently founded Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew. At the Tower of London, whose menagerie housed various exotic animals, Wolfgang was terrified by the roaring of the lions, while Nannerl was bemused by “a donkey with coffee-coloured stripes” (in reality a zebra). They met composers such as Johann Christian Bach (with whom Mozart formed a lasting bond), Karl Friedrich Abel, Thomas Arne and his son Michael, Samuel Arnold, George Rush and Mattia Vento, singers such as Giovanni Manzuoli (who is thought to have given the young Wolfgang singing lessons), Ferdinando Tenducci, Teresa Scotti, Ercole Ciprandi and Charlotte Brent, and various counts, duchesses and other aristocrats. This last category included Lady Clive, at whose home Wolfgang and Nannerl gave a recital in March 1765; it was in this same house that her husband, Lord Clive of India, was to commit suicide ten years later.

More important than any of these visits and meetings, however, was the vast array of music that the young Mozart was discovering – at the theatres at Covent Garden, Drury Lane and the Haymarket, at the Pleasure Gardens at Ranelagh, Vauxhall and Marylebone, and at the newly launched Bach-Abel concert series and various other house concerts. He was also developing rapidly as a composer in his own right, and a concert which he and his sister gave at the Little Theatre on the Haymarket on 21 February advertised that “all the Overtures [a term which at the time was interchangeable with ‘symphonies’] will be from the Composition of these astonishing Composers, only eight Years old”. The use of the plural was probably a mistake – certainly no compositions credited to Nannerl have survived, and an advertisement for the Mozart’s final public concert in London, which took place at Hickford’s Great Room in Brewer Street on 13 May 1765, promised “all the OVERTURES of this little Boy’s own Composition”.

Leopold Mozart seems to have overestimated the potential to make money, though, in a city where so many other highly capable musicians were trying to do the same thing. Unlike in the other musical centres with which he was familiar, the musical scene in London was based on commercial entrepreneurship rather than courtly favour, and as such the market-place was overcrowded. With the lengthy and expensive return journey to Salzburg looming, and wealthy interest in his children’s remarkable talents waning, Leopold resorted to increasingly desperate means of earning money. Between April and June visitors were invited to call on the Mozarts’ lodgings in Thrift (Frith) Street, where for five shillings they could have the chance to put Wolfgang’s talents “to a more Particular Proof, by giving him any Thing to play at Sight”, and by July, when he rented a room at the Swan and Hoop tavern in Cornhill (then, as now, in the financial centre of the city), the price for hearing the children perform had dropped to two shillings and sixpence.

A far more thorough and reputable examination of Wolfgang’s prodigious gifts was carried out by the Honourable Daines Barrington, an esteemed scientist, lawyer and music lover, who in 1769 submitted his findings to the Royal Society in London. This report has become one of the most valuable documents relating to Mozart’s uniquely precocious gifts, and extracts from it can be found on pages 46 and 52-53 of this booklet. Another important event from the Mozarts’ final weeks in England was their visit to the British Museum. Children were officially prohibited, but Wolfgang was invited to present to the museum printed copies of the sonatas dedicated to Queen Charlotte (K.10-15), a family portrait and one of his musical manuscripts – this was a short unaccompanied anthem, “God is our Refuge”, K.20, which proved to be his only full setting of the English language.

The Mozarts left London on 24 July 1765, travelling to Canterbury and staying for several days at the nearby Bourne Place as guests of a certain Horace Mann. From there they proceeded to Dover, and at ten o’clock on the morning of 1 August they set sail for Calais. Although Wolfgang maintained a lifelong allegiance to England – in a letter of 1782 he described himself as an “out-and-out Englishman” – he was never to return.

© Ian Page